One of the most disturbing aspects of antibiotic resistance is the discovery that genes for resistance are often contained on a plasmid, a small piece of DNA that is not part of a bacterial chromosome. These plasmids move freely within the bacterial world, jumping from one bacterium to another and even to other species of bacteria, and can increase the spread of antibiotic resistance around the globe.

In 2015, Professor Timothy Walsh and his team at the University of Cardiff, along with collaborators in China, identified a gene called mcr-1 that allowed bacteria to survive an antibiotic known as colistin. This ground-breaking discovery shook the infectious disease field, as it meant that certain bacterial infections would be impossible to treat with any of the antibiotics we currently have, a scenario described as the ‘post-antibiotic future’.

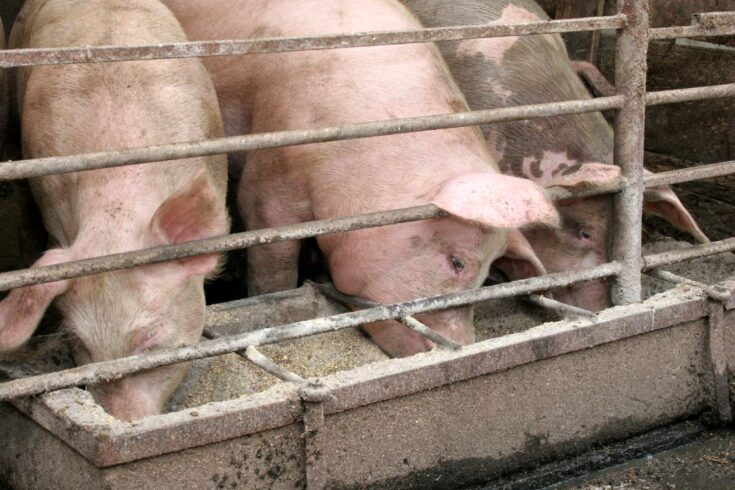

China is one of the world’s biggest users of colistin in agriculture, primarily in animal feed as a growth promoter. It is likely that colistin resistance evolved in this context. Although originally identified in China, mcr-1 has since been reported in more than 30 countries including the UK, spanning four continents.

About the project

Professor Walsh is a world-renowned expert in the spread of antibiotic resistance in a group of bacteria known as Gram-negative bacteria. In 2010, he was part of a team that reported a newly identified gene (ndm-1) that confers multidrug resistance, and was linked to travel between Europe and South Asia, especially for medical tourism.

With MRC funding, in 2011 Professor Walsh continued studying antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Infections with Gram-negative bacteria are usually treated with a class of antibiotics known as beta-lactam drugs. Since Gram-negative bacteria have become resistant to most other antibiotics, drugs called carbapenems (the most powerful beta-lactams) are now used to treat these infections.

Strains of several Gram-negative bacteria resistant to carbapenems have been identified over the past few years, notably ndm-1. For these infections, colistin is used as a ‘last resort’. For example, it is one of the few antibiotics able to treat ndm-1 positive bacterial infections. With the identification of colistin-resistant bacteria, tackling antibiotic resistance has become an even more urgent global priority.

Impacts of the project

By working closely with the Chinese government, the team influenced an unprecedented policy change. This led directly to the withdrawal of more than 24,000 tonnes of colistin from the Chinese veterinary sector.

This policy change has had wide-reaching impact, leading to a decline in colistin resistance in both animals and humans in China. It has also led to a drop in human transmission of the colistin-resistance gene.

In 2019, India also banned colistin in animal feed in line with the EU, US, Brazil and China.

Find out more

Read the journal article Changes in colistin resistance and mcr-1 abundance in Escherichia coli of animal and human origins following the ban of colistin-positive additives in China in The Lancet.