The UK will be at the forefront of new detector technology developments for the next powerful particle accelerator, the Electron-Ion Collider (EIC) in the US.

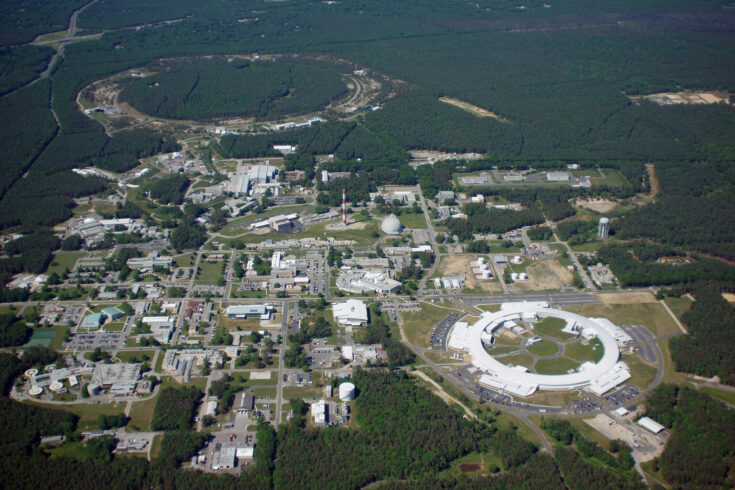

The EIC will be built at Brookhaven National Laboratory and will provide answers to some of the most fundamental questions in science on the nature of matter.

With £3 million funding through the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), nuclear and particle physicists in the UK will be leading preliminary work to help design the detectors at the new facility.

Force of nature

The EIC will be the world’s first collider of polarised electrons with polarised protons or polarised light ions. It will also be the world’s first collider of polarised electrons with heavy nuclei.

This new facility will allow scientists to image, in exquisite detail, the quarks and gluons that are found inside protons and atomic nuclei. Scientists will be able to study not only how they are distributed but also how they move and interact with one another.

The science that will be enabled by the EIC promises to revolutionise our understanding of the strong interaction, one of the fundamental forces of nature. This force governs the behaviour of hadrons, the family of subatomic particles that includes protons and neutrons, and is behind more than 99% of the visible mass of the universe.

Scientists will use the EIC to try to find out how the strong interaction works as a glue to hold matter together.

World-class expertise

Over two and a half years, this funding will position the UK to lead the development of some of the cutting-edge detector technologies that will enable the science.

The UK’s world-class expertise in the areas of silicon trackers, pixel sensors and polarimetry (a technique used to measure the orientation of a particle’s spin) will all aid this research and development programme.

There are three work packages associated with this project:

Monolithic Active Pixel Sensor (MAPS) technology

Development of tracking detectors based on state-of-the art MAPS technology. These are exceptionally thin silicon detectors with high position resolution and covering a large area to act like a powerful digital camera, capturing the products of the collisions in exceptional detail.

This work package is led by University of Birmingham and involves:

- the universities of Brunel, Lancaster and Liverpool

- STFC’s Particle Physics and Technology Departments at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory and the Nuclear Physics Group at Daresbury Laboratory.

Silicon-based detector arrays

Development of smaller silicon-based detector arrays for particle tracking in challenging regions of very high intensity, requiring excellent rate capability and timing resolution.

This work package is led by the University of Glasgow, working closely with:

- members of the CERN, Timepix4 collaboration

- STFC’s Nuclear Physics Group at Daresbury Laboratory.

Precision nucleon polarimetry

Technology evaluation and advanced simulation developments for precision nucleon polarimetry. This work package is led by the University of York.

Impactful research community

STFC Associate Director, Nuclear Physics, Justin O’Byrne said:

The UK nuclear physics community is a small yet highly impactful research community, and is internationally recognised for its leadership and expertise.

This early work will ultimately influence the capabilities and the scope of the experiment, and therefore the results that will come out of it.

Through this funding, we are positioning UK scientists to take a strong leadership role in influencing what the EIC detectors will be.

The role of the detectors

The EIC is like a high-energy electron microscope but with the ability to explore the internal structure of protons and nuclei. Detectors must be able to pick up the scattered electrons and any particles produced in each collision with high precision so that scientists can construct an accurate picture of what is found inside.

The detailed design and capabilities of the detector are currently being defined, meaning UK scientists have a chance to lead the way in deciding what this detector will be able to do.

Professor Peter Jones from the University of Birmingham said:

The EIC promises to answer some longstanding science questions about the origin of mass and the spin of the nucleon. It also has the potential to shine a light on what happens when atomic nuclei fill up with gluons.

It is incredibly exciting to be involved at the start of new major international project and to be developing some of the detector technologies required to address these questions in collaboration with our international partners.

Dr Daria Sokhan from the University of Glasgow said:

The EIC is like a scalpel for the proton and the nucleus. Its combination of unprecedented collider luminosity and polarised beams push the precision frontier. This will enable measurements of extremely rare processes and provide a wealth of crucial information about the structure of hadrons and nuclei that could not be accessed before.

It is a fantastic opportunity to help define and be involved in the development of the world’s next leading hadron physics facility at this critical, early stage, where we, and our teams and colleagues, can really make a difference.

It is expected that construction of the accelerator and its detectors will commence around 2023 to 2024, once the technical design is complete.

The first-year funding was approved under the UK Research and Innovation infrastructure fund. The funding does not equate to a full commitment to the EIC, a decision on which is expected to come in the future.