While a number of factors have contributed to the decline in elephant population over the last hundred years, poaching elephants for ivory remains a problem for their conservation.

Around 55 African elephants a day are killed for their ivory according to the World Wildlife Fund.

By making it easier to tell the difference between elephant and mammoth ivory, we can prevent illegal ivory from being traded under the guise of legal ivory.

In turn, this can deter those willing to sell ivory from animals unlawfully poached, and make trading elephant ivory less desirable.

What are the rules on trading ivory?

Most countries worldwide have implemented bans on the trade of elephant ivory, though these often have loopholes for antique ivory and items of cultural significance.

Around 70% of the world’s ivory trade occurs in China and Hong Kong. In these regions, ivory has traditionally been seen as a precious commodity, and is used in the manufacture of ornaments, jewellery and in traditional medicines.

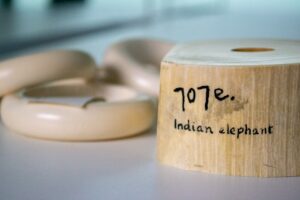

Elephant ivory samples on loan from the Natural History Museum, London. There are several carved bangles of African elephant ivory, and a polished cross section of a tusk of Indian elephant. The samples have numbers etched into them from when they were confiscated by customs in 2002. Credit: Ben Booth

The UK has one of the toughest bans on elephant ivory sales in the world with trade in elephant teeth and tusks made illegal, punishable by fines of up to £250,000 or up to 5 years in prison.

But it is also not illegal to sell ivory from animals that are already extinct, such as the Woolly Mammoth. This poses problems for law enforcement.

As global temperatures rise, the Siberian permafrost is melting and exposes more and more exceptionally well-preserved mammoth carcasses. This has led to a lucrative industry built around so called ‘mammoth hunters’. These are individuals who traverse the Siberian plains during the summer months in order to retrieve the ivory from thawing mammoths.

What are the current methods for identifying ivory?

It is possible to tell the difference between elephant and mammoth ivory in its natural state, but once samples have become worked or carved this becomes much harder.

The gold standard methods of identification recommended by The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime for assessing the legality of ivory predominantly focus on DNA and mtDNA analysis and isotope analysis – methods that are expensive, destructive and time-consuming.

We have developed a better method

Dr Rebecca Shepherd, the lead researcher on the project, holding a sample of mammoth ivory. Credit: Ben Booth

Our research uses a non-destructive, laser-based technique to identify biochemical differences in the tusks from elephants and mammoths.

The technique, known as Raman spectroscopy, has been widely used in the field of bone biology. It can even give assessments of bone health by shining a light through the skin of a patient. The technology is widely available, and already used at customs centres worldwide in the identification of powders and chemicals.

Raman spectroscopy works by shining a high energy light at a sample:

- the molecules in the sample temporarily absorbs the energy from the light, and then releases it

- the amount of energy released by the molecules is either slightly more or slightly less than the original energy

- different types of molecules have a different ‘fingerprint’ of energy that is released

Rebecca Shepherd in the lab with scanned samples of elephant and mammoth ivory. Credit: Rebecca Shepherd

It is these differences that allows us to use Raman spectroscopy to differentiate between materials. Although mammoths and elephants are from the same family tree, there will be small differences in the biochemistry of their tusks. Our previous work, using ivory samples obtained from UK museums, looked to identify where the greatest differences in the biochemical make up of tusks occurred.

We have previously scanned samples of elephant and mammoth ivory to study the differences in their biochemical composition. While the equipment we have set up is large, smaller and more portable Raman spectrometers are readily available.

We have been awarded an EPSRC Impact Acceleration Award to work with our collaborators at Worldwide Wildlife Fund Hong Kong to expand our database of current ivory samples and create software that can use Raman spectroscopy data from ivory of unknown origin and suggest from which species it has been taken.

What difference will this make to wildlife conservation?

On completion of this project, it is hoped that we can release the software created for free use worldwide.

The potential to have an immediate and meaningful impact on wildlife conservation with this project is clear.

Sadly, a complete ban on all ivory trade around the globe is unlikely. The best way to prevent the trade of ivory from endangered animals is to enable law enforcement to act on current legislations and appropriately punish those in breach of regulations. This could help protect declining elephant populations, and, we hope, help to prevent them from becoming extinct within the next 20 years.

You can follow my work on Twitter: @special_stains